, I've been posting my subjective opinions (aren’t they all?) on live action iterations of the Superman family, rating them from favorite (#1) to least. I'm reposting the series here, comprised of looks at Ma and Pa Kent, Supergirl, Lana Lang, Jor-El and Lara, Perry White, Jimmy Olsen, Lex Luthor, Clark Kent, Lois Lane, and Superman (separating Kal-El into his two identities for some reasons).

If a character only appeared as a small cameo or in just an episode or two (eg, Ma Kent in SUPERMAN & LOIS or “Jimmy Olsen” in BVS), that may not have been enough to make an impression (then again, in some cases it did!). Likewise, if I’ve never SEEN a specific performance (eg, Lana Lang or Jor-El and Lara in LOIS AND CLARK or Jon Cryer as Lex Luthor in SUPERGIRL), then I can’t have an opinion (unlike many people on the Internet who don’t abide by such criteria). And while I didn’t include SuperBOY on this list, I did so for the portrayals of his alter ego (mostly for one important performance).

Following our look at characters, over the next ten days from July 1-10, I’ll be rating my favorite to least favorite live action Superman movies leading up to the official release of James Gunn’s SUPERMAN (where that movie will fit is something I probably won’t be able to answer for a while). I'll post those after I'm finished...

#1 and 2 were a toss-up on this list. Obviously, SMALLVILLE benefitted from Jon and Martha being a major part of the story for its entire run, allowing for a much deeper characterization than most adaptations. But Ford & Thaxter made such an indelible impression as the main reason that Clark decides there’s no other option for his abilities than to help people (even if does mean interfering with human history).

Jones & Callan were one of the only aspects of LOIS & CLARK that worked for me. And I always found the “Gee Whillikers” simplicity of the Kents in the serials and the Reeves series’ initial installments to have a certain charm that made them both memorable. Eva Marie Saint didn’t have much to do but silently react to the sad happenings in RETURNS, but she was fine.

And then we have #7. Not just my least favorite version of Ma and Pa Kent, but one of my biggest issues with this take on Superman. Jonathan and Martha’s paranoia and fear of potential exploitation or persecution of their adopted son, encouraging him to hide his powers to the extent of suggesting “maybe” he should’ve let that busful of his classmates drown, like so many other parts of MAN OF STEEL, just shows a fundamental misunderstanding of what makes Superman Superman. “You don’t owe these people a damn thing” does not evoke sacrifice and altruism so much as it does selfishness and cynicism. And that ain’t Jonathan and Martha Kent, no matter how “realistic” you try to make them.

Also, Clark totally could’ve saved Jon from that tornado. That’s just dumb.

My advance thoughts on Pruitt Taylor Vince and Neva Howell based on what we’ve seen so far? Not sure how I feel about the heavy accent, but they seem to have their hearts in the right place, which is, of course, the whole point.

SUPERGIRL

1. Melissa Benoist SUPERGIRL (TV) / 2015-21

2. Helen Slater SUPERGIRL / 1984

3. Laura Vandervoort SMALLVILLE / 2007-11

4. Sasha Calle THE FLASH / 2023

It’s kind of amazing that in the 67 years since she was introduced to the mythos, Superman’s cousin has only been adapted to live action four times (and only three in costume and name). For all of the many issues with the character’s film debut, Helen Slater’s Kara Zor-El had an innocence and charm to her that made it possible to imagine she was related to Chris Reeve’s Superman (too bad they only met via weird CGI in THE FLASH).

Same can be said of my #1 pick. TBH, I was not a fan of the so-called Arrowverse, I found its reliance on soap operatics (so much crying in those shows!!) and season-long story arcs to be mostly tiresome. I tried with all of them, but never made it more than a few seasons (I’d dipped out of SUPERGIRL before she got her pants suit and Jon Cryer came on board as Lex Luthor). But I did really like Benoist as Kara, much as I wish her television milieu had been handled differently.

Laura Vandervoort’s Kara on SMALLVILLE was fine, but was hamstrung by the series’ inherent storytelling limitations. You couldn’t have Supergirl before you had Superman, so even though her powers were initially more developed, she had to pretty much stay in the shadows (hey, just like the comics!).

And as for Sasha Calle’s Supergirl from that last gasp of the DCEU, well, Kara, we hardly knew ye.

I have high hopes for Milly Alcock’s version of the character, as one of my favorite retcons of the Superman lore is that Kara is a far more tragic, damaged figure than her well-adjusted cousin, having been old enough to experience the PTSD of you know, losing your entire planet. It makes her more than a gender swapped carbon copy of Superman, and allows for some nice conflict. Fingers crossed.

LANA LANG

1. Stacy Haiduk SUPERBOY (TV) / 1988-92

2. Annette O’Toole SUPERMAN III / 1983

3. Emmanuelle Chriqui SUPERMAN & LOIS / 2021-24

4. Diane Sherry SUPERMAN THE MOVIE / 1978

5. Kristin Kreuk SMALLVILLE / 2001-11

Like Supergirl, Clark’s teenage crush / pal has only been adapted a few times, but they’ve mostly been pretty memorable (Bunny Henning from the 1961 SUPERBOY pilot didn’t make the list because I’ve only watched that once or twice). Diane Sherry was a blip as Lana in 1978’s SUPERMAN (and also kind of a jerk, at least in the theatrical cut), but Annette O’Toole’s depiction of the adult version of her in SUPERMAN III was one of that movie’s highlights (even if the struggling single mom angle and a general lack of Lana’s usual pluck made her feel like the character in name only).

Kristin Kreuk was fine as Lana in SMALLVILLE. I guess. I just never warmed to that actress (particularly in contrast to Clark’s later love interest in that show, as we will see). Emmanuelle Chriqui played perhaps the most fleshed-out version of the character on SUPERMAN & LOIS, and I really believed the depth of her friendship with Clark (which made the drama surrounding his identity revelation to her emotionally resonant).

But, as with so many men of a certain age, my favorite version of Lana Lang was from the syndicated SUPERBOY TV show, a series that tried really hard, but the missed the mark in almost every way (often through no fault of its own besides a minuscule budget). Stacy Haiduk (the only actor to make it through the entire series) was not just stunning, she managed to find a seemingly impossible balance of damsel in distress and strong, independent young woman. She wasn’t just the best part of the show, she made it worth watching.

With all the supporting characters populating the new SUPERMAN, I’m kinda surprised Lana didn’t make the cut (maybe in her TV reporter role as she was in the Bronze Age comics). Or will she? Time will tell.

JOR-EL AND LARA

1. Russell Crowe & Ayelet Zurer MAN OF STEEL / 2013

2. Marlon Brando & Susannah York / SUPERMAN, II / 1978-82

3. Robert Rockwell & Aline Towne ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN 1952

4. Nelson Leigh & Luana Walters SUPERMAN, ATOM MAN VS. SUPERMAN / 1948-50

5. Angus McFayden & Mariana Klaveno / SUPERMAN & LOIS / 2021-24

6. Julian Sands & Helen Slater, SMALLVILLE / 2009-11 / 2007-11

See? I’m not intractable when it comes to the Snyderverse! When I saw MAN OF STEEL for the first time in 2013, the opening on Krypton gave me false hope for what would unfold over the next few hours (aside from those comical dildo Phantom Zone conveyances and the choice of the word “Codex” for the planetary DNA... Seriously, wtf were they thinking?). Russell Crowe and Ayelet Zurer (now the Kingpin’s evil wife on DAREDEVIL) Russell Crowe and Ayelet Zurer (now the Kingpin’s evil wife on DAREDEVIL) made formidable versions of Jor-El and Lara, dealing with more than “just” the imminent destruction of their planet.

Brando and York could’ve been in the #1 spot just from an iconographic standpoint, but I can never get over Brando’s mispronunciation of “Kriptin” and knowing that he was reading his lines off of baby Kal’s diaper. Their portrayals influenced many of those that followed, including some that are not on this list that I’d only seen in clips or in long-forgotten episodes of shows I didn’t love, as well as the last pairing on this list, which didn’t really make an impact (at least as much as Terence Stamp’s voicing of Jor-El in the show, which I always thought was a weirdly incongruous casting choice).

As with the 1940s/50s Ma & Pa Kent, I also love the incredibly retro sci-fi depictions of the Els from the serials and ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN (Jor-El even wears Flash Gordon’s suit in the TV pilot!), just oozing that DIY inventiveness of genre filmmaking of the time. There’s a similar throwback vibe in Angus McFayden and Mariana Klaveno’s Jor-El and Lara from SUPERMAN & LOIS, even though we only ever saw them as AI holograms (as overdone as it was, I kinda wish we’d had a flashback to them on Krypton in one episode).

James Gunn’s been adamant that he’s not going to rehash elements of the Superman mythos that are already ingrained in the public consciousness, so we may not ever get to see his version of the El family, but if we do, I bet they’re wearing green and yellow!

PERRY WHITE

1. John Hamilton ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN / 1952-58

2. Jackie Cooper SUPERMAN - IV / 1978-87

3. Frank Langella SUPERMAN RETURNS / 2006

4. Pierre Watkin SUPERMAN, ATOM MAN VS. SUPERMAN / 1948-50

5. Laurence Fishburne MAN OF STEEL et al / 2013-17

6. Michael McKean SMALLVILLE / 2003-11

7. Lane Smith LOIS AND CLARK: THE NEW ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN / 1993-97

We’re halfway done with our survey of the live action Superman family, today saying Hail to the…

DON’T CALL HIM CHIEF! Perry White, the gruff, no-BS editor of the Daily Planet is not just a great character, he’s gotta be one of the most fun in the Superman lore for an actor to play (and most have done some real scene—and cigar—chewing with him).

The character emerged fully formed in live action, as Pierre Watkin brought a combination of authority and annoyance to the role in the two Columbia Serials. But the next actor took it to the next, untopped level: John Hamilton in TV’s ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN is probably forever Perry White to anyone who grew up with that show (either new or in reruns). His short temper and sarcastic yet authoritative demeanor tempered with an obvious intelligence made for one of that show’s two pitch-perfect castings.

Similarly, Jackie Cooper (a last minute replacement for Keenan Wynn) was utterly believable and engaging in SUPERMAN THE MOVIE, giving the film as much gravitas as Brando and Hackman (seeing the actor’s decline over the four films was kinda heartbreaking). Subsequent movie Perrys (Perries?) Frank Langella and Laurence Fishburne are both terrific actors who were sadly given very little to do in their respective films, but I’m psyched to see the great Wendell Pierce give it a go in the new film.

The other small screen iterations were less impactful. On SMALLVILLE, Michael McKean’s pre-PLANET tabloid reporter who eventually goes legit and ends up dating Martha Kent (!!!) not only felt shoehorned (the actor is Annette O’Toole’s husband), but was one of that show’s handful of creative missteps.

Still, no version was worse than LOIS AND CLARK’s Lane Smith, whose portrayal of the editor as a somewhat buffoonish southerner (whose catchphrase of “Great Shades of Elvis!” made me groan every time) carried the same weight as Pat Hingle’s Commissioner Gordon in the BATMAN movies of the same time. Painful.

JIMMY OLSEN

1. Jack Larson ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN / 1952-58

2. Marc McClure SUPERMAN I-IV, SUPERGIRL / 1978-87

3. Sam Huntington SUPERMAN RETURNS / 2006

4. Tommy Bond SUPERMAN, ATOM MAN VS. SUPERMAN / 1948-50

5 (TIE). Justin Whalin / Michael Landis LOIS AND CLARK: THE NEW ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN / 1993-97

6. Mehcad Brooks SUPERGIRL (TV) / 2015-21

The second half of our look at the live action Superman family begins with Daily Planet cub reporter / photographer, Superman’s pal, Jimmy Olsen! And we’re just gonna go ahead and declare that no actor will ever take the crown from the iconic Jack Larson in ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN. Sure, he was goofy and played it broad, but Larson’s earnestness, immense likability, and impeccable comedic timing made the character so popular, he got his own comic book!

Marc McClure, like his Clark Kent co-star, managed to make an “aw-shucks” innocence not seem anachronistic in the ‘70s setting of SUPERMAN THE MOVIE, but, MAN, I wish he’d been given more to do in those films. Likewise with SUPERMAN RETURNS’ Sam Huntington, a more successful throwback casting than anyone else in that movie.

Tommy Bond played Jimmy in the serials with a bit of an edge, perhaps a holdover image from his years as Butch in the OUR GANG shorts. Neither actor who played the character on LOIS AND CLARK made much of an impact on me (and while Aaron Ashmore was okay on SMALLVILLE, concerns about him being the same age as Clark resulted in the revelation at the end of the series that he wasn’t actually the “real” Jimmy Olsen, but rather his older brother Henry, hence his absence from this list).

But for me, the worst Jimmy Olsen was Mehcad Brooks on SUPERGIRL (and NO, not because he wasn’t white!!). This tall, handsome, imposing James Olsen simply had not one single character trait in common with his comic inspiration (aside from being Superman’s pal), even becoming both the superhero the Guardian and (for a while) a romantic interest for Supergirl! The character was not bad, but he sure wasn’t Jimmy Olsen.

As for Skyler Gisondo, our new Jimmy, he hasn’t really been in the advance material, so who knows (and will we EVER have a red-haired Jimmy Olsen? At least he's got the freckles!)

CLARK KENT

1. Christopher Reeve, SUPERMAN THE MOVIE - IV / 1978-87

2. Tom Welling, SMALLVILLE / 2001-11

3. Tyler Hoechlin, SUPERMAN & LOIS / 2021-24

4. Kirk Alyn, SUPERMAN SERIALS / 1948-50

5. George Reeves, ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN / 1952-58

6. Brandon Routh, SUPERMAN RETURNS / 2006

7. Henry Cavill, MAN OF STEEL et al / 2013-22

8. Gerard Christopher, SUPERBOY / 1989-92

9. Dean Cain, LOIS & CLARK: THE NEW ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN / 1993-97

10. John Haymes Newton, SUPERBOY / 1988-89

Winding down the list of live-action Superman characters with the not-always-mild-mannered reporter for the Daily Planet… this being the demarcation with most fans; Do you like your Clark Kent meek or bold?

I prefer the former, so obviously, no performance holds a candle to Christopher Reeve’s, an acting job so pitch perfect that (despite my antipathy towards such things) it’s a crime he wasn’t awarded any shiny statues. Reeve convinced a cynical 1970s audience that maybe people actually wouldn’t realize who it was behind the horn-rims. And despite the diminishing returns of the SUPERMAN series, his Clark remained an enjoyable constant.

My #2 pick, Tom Welling, proved himself over SMALLVILLE’s decade to be way more than just a pretty face; He brought a depth, integrity, and sensitivity to Clark that (especially paired with our top Luthor from yesterday) made the coming-of-age story feel genuine and meaningful.

Of the other actors on this list, only Kirk Alyn, Brandon Routh, and Gerard Christopher played Clark differently than they did Superman (/boy), with mixed results. Everyone else followed the undeniably iconic, but rather mud-stuck George Reeves’ refusal to subjugate Superman’s Alpha under a Beta Clark. Tyler Hoechlin may have embraced the humble farm boy aspect of Clark, but he also played Superman the same way (neither of them remembering to shave). Given that Henry Cavill’s Clark was constantly being told he needed to hide from humanity, you’d think that he’d have chosen the mild-mannered persona, but I’m guessing Zack Snyder thought was too uncool, dude. And (spoiler alert for our #1 list) nothing, and I mean NOTHING about Dean Cain ever said Clark Kent OR Superman to me (even way before the actor’s politics made him anathema to everything Superman represents).

Oh, and John Haymes Newton. Right.

SO, Corenswet’s broccoli hair is a tough tackle, but I really like the nuances that I’ve seen in his Clark Kent thus far… and we finally get to see him tussle with Steve Lombard!

LEX LUTHOR

1. Michael Rosenbaum / SMALLVILLE / 2001-11

2. Gene Hackman SUPERMAN THE MOVIE, II, IV / 1978-87

3. Lyle Talbot ATOM MAN VS. SUPERMAN / 1950

4. John Shea LOIS AND CLARK: THE NEW ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN / 1993-97

5. Sherman Howard SUPERBOY / 1989-92

6. Kevin Spacey SUPERMAN RETURNS / 2006

7. Scott Wells SUPERBOY / 1988-89

8. Michael Cudlitz SUPERMAN & LOIS / 2023-24

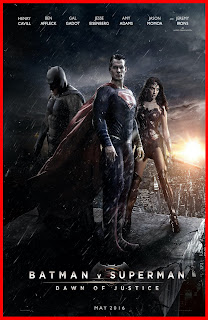

9. Jesse Eisenberg BATMAN V SUPERMAN: DAWN OF JUSTICE / 2016

Day 8 of our examination of live-action Superman characters tackles Superman’s #1 arch enemy, Lex Luthor, a character who’s been played with a wider range of personality—and success—than any other on this list.

Gene Hackman’s undeniably magnetic, but borderline campy Luthor may be the most iconic, but always felt more like a movie construct than an adaptation of the comic book villain (I mean, should Lex Luthor be beloved?). Lyle Talbot in ATOM MAN VS. SUPERMAN looked more like him than any other version, but it was Michael Rosenbaum’s incredibly nuanced performance in SMALLVILLE as teenage Clark Kent’s frenemy, a tortured soul with a simmering darkness building over his seven seasons on the show, that stands as the most complex—and ultimately terrifying—depiction of Luthor.

TBH, not ONE of the other six actors on this list really worked for me. LOIS & CLARK’s John Shea tried to evoke the Byrne-era Luthor, but lacked any malevolent gravitas. Of the Lexi on SUPERBOY, Scott Wells was laughably bad, while Sherman Howard seemed to leap out of a Looney Tunes cartoon (which sometimes worked). Master Thespian, Kevin Spacey… well, you know. And I have no idea who the hell the Ministry-lovin’ biker thug Michael Cudlitz played on SUPERMAN AND LOIS, but it sure wasn’t any Lex Luthor I recognized (and for the record, I’d stopped watching SUPERGIRL before Jon Cryer came on as the villain, but I hear good things).

But few would argue that the most ill-advised casting and least successful take on Lex Luthor was Jesse Eisenberg in BVS:DOJ. The young, neurotic, candy-sucking industrialist with confusing motivation beyond a narcissistic drive for world domination that felt straight out of an episode of SUPER FRIENDS was literally painful to watch in every single scene through which the Zuckerbergian foe chewed. Mercifully, we were spared more than a few cameos beyond this trainwreck.

So, Nicholas Hoult? I was skeptical when I heard the casting, but goddamn if he doesn’t seem to have the goods in the trailers… fingers crossed.

LOIS LANE

1. Erica Durance SMALLVILLE / 2004-11

2. Margot Kidder SUPERMAN THE MOVIE - IV / 1978-87

3. Phyllis Coates SUPERMAN AND THE MOLE MEN / 1951, ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN 1952-53

4. Teri Hatcher LOIS AND CLARK: THE NEW ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN / 1993-97

5. Bitsie Tulloch SUPERMAN & LOIS / 2021-24

6. Noel Neill SUPERMAN SERIALS / 1948-50, ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN 1953-58

7. Amy Adams MAN OF STEEL et al / 2013-17

8. Kate Bosworth SUPERMAN RETURNS / 2006

It’s the final two days of our live-action Superman family ratings, today tackling the tenacious reporter with a penchant for purple, Lois Lane!

Honestly, for me #1 and #2 are probably a tie. Margot Kidder’s iconic Lois in SUPERMAN was feisty, formidable, and utterly lovable (even if she smoked and couldn’t spell), and her chemistry with Chris Reeve was a HUGE part of that film’s success. But man, I just fell hard for Erica Durance’s surprisingly indelible portrayal on SMALLVILLE, in which her inclusion initially felt rushed, but quickly became one of the high points of the show. Durance captured Lois’ brashness (at times bordering on reckless) better than anyone to date. And she was HOT.

While Noel Neill was the first (and longest running) live depiction of Lois, she never evoked the grit and fire that I felt would make her irresistible to the Man of Steel (Phyllis Coates was way tougher). Teri Hatcher was hands down the best thing about LOIS AND CLARK, and deserved much better than that wrong-headed take on the saga. Bitsie Tulloch on SUPERMAN AND LOIS wonderfully portrayed the character’s strength and love for Clark, but, subjectively, the whole “Super Parents” angle just isn’t my preferred version of the story.

As for Amy Adams, I had high hopes, but while she convinced me she was a bad-ass journalist, I just never once bought into her relationship with Superman / Clark (saying they lacked chemistry is putting it mildly). And I will never understand how Bryan Singer thought the cardboard cutout that is Kate Bosworth could ever capture the fire of Margot Kidder’s Lois.

Now, here’s where I break tradition and make a prediction: This time next month, I’ll have a new favorite Lois Lane. To me, Rachel Brosnahan is PERFECT casting as Lois Lane, and I cannot wait to see her fulfill that destiny. Bravo, James Gunn.

SUPERMAN

1. Christopher Reeve SUPERMAN - IV / 1978-87

2. George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN 1952-58

3. Tyler Hoechlin SUPERMAN & LOIS / 2021-24

4. Henry Cavill MAN OF STEEL et al / 2013-2022

5. Brandon Routh SUPERMAN RETURNS / 2006

6. Kirk Alyn SUPERMAN SERIALS / 1948-50

7. Dean Cain LOIS AND CLARK: THE NEW ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN / 1993-97

HONORABLE MENTION: Brandon Routh CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS / 2019-2020

Finishing up our survey of the live-action Superman family to date with our titular hero, and anyone who’s been paying attention knows my #1.

For me, nobody will EVER top Christopher Reeve’s portrayal of the Man of Steel in SUPERMAN THE MOVIE, the best (and most miraculous) casting in the history of the genre.* Reeve GOT the character, understanding that the super powers are secondary to the values instilled in him by his adopted parents. When he tells Lois that he’s “A friend,” it’s the most defining few seconds in the history of live action Superman. Reeve had charm, gravitas, and (bags of) humility, all at the age of 25! To millions, he’ll always be Superman.

I’m old enough that George Reeves was my first live Superman (in reruns), and while even as a kid, I could tell that ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN was of a different time, the show retained much of its appeal, largely because of Reeves’ robust (if somewhat avuncular, right down to the graying temples) Supes.

Tyler Hoechlin didn’t impress me on SUPERGIRL, so I was surprised at how much I loved his take on SUPERMAN AND LOIS, understated yet powerful, friendly but formidable. I’m bummed the show was prematurely cut short.

Henry Cavill… well, as I’ve said before, I like the guy. I think he had the goods. But sadly, he was shoved into the most wrongheaded take on the character in his long and storied history. Say what you will about JUSTICE LEAGUE, at least he got to crack a few smiles in that one.

Brandon Routh? As the Chris Reeve Superman? Nah, didn’t work. As the older KINGDOM COME Superman? Much better. And Kirk Alyn’s theatricality was hit or miss, but the seminal nature of his portrayal carries a lot of weight.

And then there’s Dean Cain. Worst. Superman. Ever. (Onscreen AND off.)

How do I feel about David Corenswet, just over a week out? That first full trailer really silenced a lot of doubts, but—unlike with Lois—I’m reserving judgment. Maybe it’s that I still can’t get behind that costume. But the clothes don’t really make the man, now do they?

* Runners-Up include Robert Downey Jr. as Iron Man, Lynda Carter as Wonder Woman, Chris Evans as Captain America, Jackie Earle Haley as Rorschach, and most of the primary villains on BATMAN 1966!

Originally posted on Instagram, June 21-30, 2025